By Alan Johnstone

Workers’ struggles fill many of the forgotten pages of American history. The great labor uprising of 1877 is a case in point.

The Great Upheaval grew out of their intuitive sense that they needed each other, had the support of each other, and together were powerful. This sense of unity was not embodied in any centralized plan or leadership, but in the feelings and action of each participant.

Jeremy Brecher, Strike!

Following the crash of 1873, by July 1877 America was still deep in the depression. The previous year the total revenues of America’s railroads fell by $5.8 million. But they still raised profits to $186 million and managed to present shareholders with 10% dividends.

As Philip S. Foner noted in The Great Labor Uprising Of 1877, the railroads reduced workers’ pay by an average of 21%–37%. The Baltimore & Ohio reduced its staff’s pay by 50%.

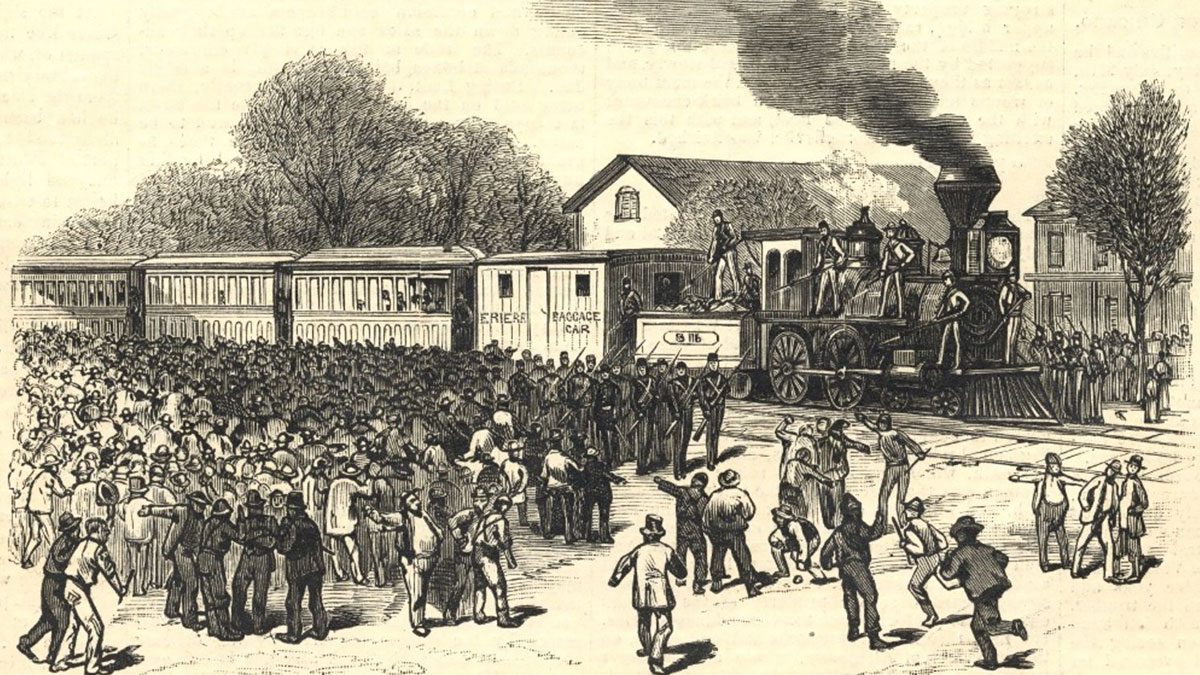

Working people had to strike to provide for their families. They could no longer endure the misery. The Great Railroad Strike began on July 13 at Martinsburg, West Virginia and the strike quickly spread across many parts of the United States, at times taking on the appearance of an insurrection. There were widespread attacks on rail company property. In St Louis workers committees and general assemblies began running things and gender and color differences were put aside. The strikes went beyond the grievances held by the railroad workers and grew into a campaign for the Eight-Hour-Day. 1877 was also the year that the army was withdrawn from the ex-Confederate states, leaving the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize the former slaves and impose the Jim Crow regime. Instead, the military was sent to put down the workers’ strikes.

East St Louis General Strike

Largely organized by the Knights of Labor and the Workingmen’s Party, in East St Louis on July 22, train workers held meetings calling for pay rises but they adopted a series of radical resolutions:

“Whereas, The United States government has allied itself on the side of capital and against labor; therefore,

Resolved, That we, the workingmen’s party of the United States, heartily sympathize with the employees of all the railroads in the country who are attempting to secure just and equitable reward for their labor.

Resolved, That we will stand by them in this most righteous struggle of labor against robbery and oppression, through good and evil report, to the end of the struggle.”

When the strike began within hours strikers had taken control of the city. One speaker declared:

“All you have to do, gentlemen, for you have the numbers, is to unite on one idea – that workingmen shall rule the country. What man makes, belongs to him, and the workingmen made this country.”

At one rally a black man asked, “Will you stand to us regardless of color?” and the audience responded resolutely, “We will”.

“Only around St. Louis did the original strike on the railroads expand into such a systematically organized and complete shut-down of all industry that the term general strike is fully justified. And only there did the socialists assume undisputed leadership…no American city has come so close to being ruled by a workers’ soviet, as we would now call it, as St. Louis, Missouri, in the year 1877.” [his emphasis]

The aftermath of July produced the Veiled Prophet Organization, a racist secret society, complete with KKK-style regalia, consisting of members of the St. Louis elite who feared the solidarity between white and black workers.

Pittsburgh

On Thursday, July 19, railroad workers brought train traffic to a halt. Iron and steel workers, miners, and many others joined the industrial action. The National Guard was mobilized but the authorities recognized that they could not be relied upon.

“Situation in Pittsburgh is becoming dangerous. Troops are in sympathy, in some instances, with the strikers. Can you rely on yours?” said a request by the local commander to higher command.

Many of the Pittsburgh town police and its local militia had sided with the strikers and were refusing to take action against them. Reinforcements were rushed in from Philadelphia and they were far less friendly towards the strikers. In an attempt to disperse a crowd, someone was bayoneted. Protesters retaliated with stones and shot pistols at the troops who returned fire and bayonet charged. When the fighting ceased, an estimated 20 men, women and children had been killed.

The news of the shooting spread. A gun manufacturer was looted and rifles and small-arms were taken by the strikers while gun stores were broken into for more weapons.

The Philadelphian units found themselves overwhelmed and retreated but in due course fresh detachments arrived from Philadelphia in addition to federal troops, and they managed to regain control. The exchanges had resulted in 53 strikers and 8 soldiers killed.

Scranton

“Whereas, we, the employees of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company, believe that we are not getting a just remuneration for our labor or a sufficient supply for ourselves and families of the common necessaries of life, therefore Resolved, That we demand twenty-five per cent advance on the present rate of wages; also it is further Resolved, That with a refusal of these demands all work will be abandoned from date, as we have willingly submitted to the reduction and without murmur or resistance and finding that it now fails us to live as becomes citizens of a civilized Nation we take these steps in order to supply ourselves and little ones with the necessaries of life.”

The strike began on July 23 when railroad workers walked off the job in protest of recent wage cuts. Railway workers were joined in the strike by coal miners and iron mill workers, and within three days it grew to include thousands of workers from a variety of industries. The employers and city officials responded with the creation of a vigilante force called the Scranton Citizen Corps.

Violence erupted on August 1 after strikers attacked the town’s mayor and then clashed with local militia, leaving four dead and many more wounded, whereupon State and federal troops were called in to impose martial law.

Reading

“There’s an army of strikers,

Determined you’ll see,

Who will fight corporations

Till the Country is free.”

The chant of the crowd

Another battleground was in Reading, Pennsylvania, where the boss of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and Coal and Iron Company, Franklin Gowen, had already proved himself to be anti-worker and anti-union. Reading Railroad was the biggest mine company in the Anthracite region. When it lowered mining wages to 54% of their 1869 level, miners began the “Long Strike” of 1875, lasting 170 days. But the company had stockpiled enough coal to outlast the strike and crushed the miners’ union. It also accused leaders of being part of the Molly Maguires, who allegedly assassinated company officials. Beginning in June 1877, 20 alleged Molly Maguires were executed, often despite strong evidence of innocence, with Catholics and Irish excluded from juries. The Reading Railroad later twice lowered miners’ wages by 10-15% between 1876 and 1877.

As for the railroad workers, the company demanded they desert the union and join the company’s insurance plan, which they would lose if they stopped working. In defiance, the trainmen went on strike in April 1877. They were replaced with inexperienced scabs who caused many accidents. Nevertheless, it finished the Brotherhood of Railroad Engineers, with most of its members dismissed and blacklisted by the company.

As a precaution on July 23, the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Police, the railroad’s private police force, arrived in Reading along with the 4th Pennsylvania Volunteer Militia, who were asked by the railroad to release a train being blocked by protesters. As the 4th marched along the tracks in the dark they were stoned by a crowd. The soldiers opened fire and left between 10 and 16 dead, and between 37 and 50 injured.

Several companies of the 16th militia regiment from Conshohocken arrived, but many supported the strikers. General Reeder, commander of the 4th, telegraphed to his superior explaining his predicament:

“My situation is not improved by the arrival of the Sixteenth regiment, which is very disaffected. The Fourth is becoming anxious, and is also very much exhausted. Should have reliable troops, without delay…The Sixteenth regiment is furnishing the strikers with ammunition and openly declare their intention to join the rioters in case of trouble. If troops do not reach us by dark, I cannot vouch for the safety of the city, or my power to hold the depot. Stir heaven and earth to forward reliable and fresh troops.”

16th soldiers began deserting and fraternalizing with the strikers, sharing in the animosity towards the 4th over the killings of the previous night.

In the words of one member of the militia: ‘We may be militiamen, but we are workmen first.’

There was a real and growing risk of an open fight between the 16th and the 4th. General Bolton telegraphed the State Adjutant General: “Have United States troops sent to Reading at once. Portion of the Sixteenth regiment are about revolting and joining the strikers”.

Angry crowds had again gathered and were throwing stones at the 4th. However, when some in the 4th aimed their rifles, the 16th shouted to them not to shoot, while some handed over their arms and ammunition to the crowd. The 16th also warned that if the 4th fired on the crowd the 16th would fire on them.

On July 24 all militia troops were withdrawn and replaced by 300 regular soldiers to ensure that the Coal and Iron Police had control of the town.

The Battle of the Viaduct

On July 26, in Chicago at the Halstead Viaduct, strikers and protesters refused to disperse and street fights began with the police, who were reinforced by militia and regular troops. At least 30 workers died, many of them mere boys, and up to 200 were wounded.

There were many other minor engagements with the employers such as that of Shamokin. On July 25, a day after the miners at the Shamokin’s Big Mountain Colliery demanded ‘Food or Work’ and protested a 10% pay cut, the urban revolt arrived when the town’s Reading Railroad’s depot was sacked and looted. A citizens militia ordered the crowd to disperse. The crowd refused and was fired upon. Many were wounded.

Conclusion

Was it an insurrection? Could it be called a labor revolution, a civil war between labor and capital? Or merely the work of a mob of rioters?

Writing to Engels on the 25th July 1877, Marx described it as the ‘first eruption against the oligarchy of associated capital which has arisen since the Civil War’ and predicted that although it would be suppressed it ‘could very well be the starting point for the establishment of a serious labor party in the United States.’

Many thought as Marx: that 1877 had been a catalyst.

The Workingmen’s Party of the United States the following year reformed itself as the Socialist[ic] Labor Party.

Two-thirds of America’s 75,000 miles of railroad track had been affected by the strikes. Millions of dollars’ worth of railroad property had been burned down, blown up or torn apart. And, for the first time in U.S. history, federal troops had been deployed in force to crush strikers.

In the aftermath, National Guard units proliferated. In many states and cities, armories, thick-walled citadels, were constructed in case anything like 1877 ever happened again. The local capitalists restructured the National Guard: instead of ‘poor men in uniform fighting poor men in overalls,’ they were now chosen from the well-to-do to ensure their class loyalty.

The July uprisings had shown the workers their strength and in the future, they would learn how to use it. It was a period in history, albeit short-lived and with varying degrees of success, when working people held power is in their hands.

In 1877, the same year blacks learned they did not have enough strength to make real the promise of equality in the Civil War, working people learned they were not united enough, not powerful enough, to defeat the combination of private capital and government power.

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States