By Alan Johnstone

Some peoples possess shamans to explain how the world works. We have charlatan economists and politicians posing as intellectuals who claim to be able to reveal the mystery of running society.

The ideas of Marx did not arise out of thin air. They grew out of the works of many others before him. But the purpose of this short essay is not to explore his Young Hegelian philosophical roots or to expound on the influence of earlier economists such as Ricardo on Marx but to focus upon the independent thought that developed within the working class and that Marx would incorporate into his own conception of the world around him.

Out of the discontent of the Industrial Revolution arose the Chartist movement. The need for the whole working class to unite in one movement had come to the fore. The Chartists was the first mass political movement of the British working class and effectively Britain’s first civil rights movement. Many unknown and, therefore, unacknowledged workers engaged in the mass struggle for the vote. As the factory and mill owners resisted any rebellion against the dictatorship of capital, certain radicals emphasized the connection between the struggle to win the vote and the class struggle. They also came to understand that this was just a part of a wider and greater international fight for democracy and people’s power.

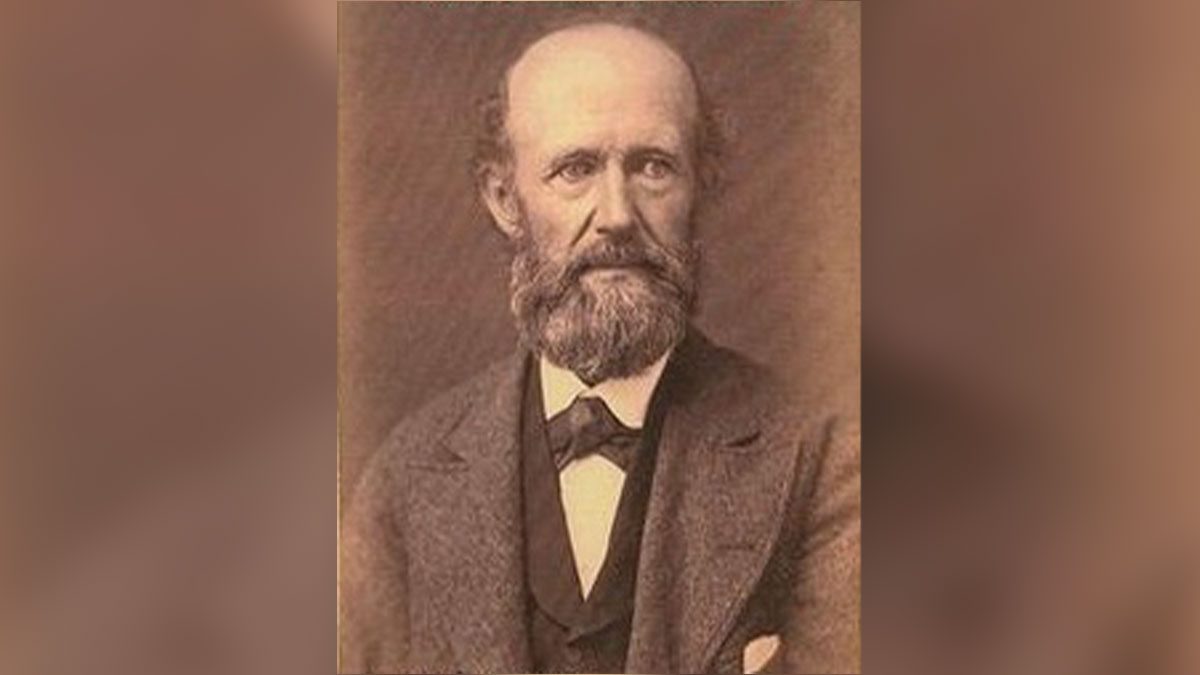

In his 1839 Labour’s Wrongs and Labour’s Remedy or The Age of Might and the Age of Right, one of the early Chartist activists, John Francis Bray, whose portrait heads this article, writes:

There is wanted, not a mere governmental or particular remedy, but a general remedy – one which will apply to all social wrongs and evils, great and small…they want a remedy for their poverty – they want a remedy for the misery…Knowledge is merely an accumulation of facts; and wisdom is the art of applying such knowledge to its true purpose – the promotion of human happiness.

In the same year as Bray published his book, George Julian Harney was dismissing the policy of appealing to the goodwill of the ruling class, rebuffing any alliances with them. Referring to the effects of the New Poor Law Act on the conditions in the workhouses, he stated:

You see now through the delusions of your enemies. Nearly nine years of ‘liberal’ government have taught you the blessings of middle class sway, blessings exemplified in ‘bastilles’ and ‘water gruel,’ in ‘separation’ and ‘starvation’; in the cells of silent horror and the chains of transportation, in the universal misery of yourselves and the universal profligacy of your oppressors (London Democrat, April 20, 1839).

It was on September 1845, two decades before the First International, that the Society of Fraternal Democrats was formed, adopting the motto All men are brethren. It was founded by some in the British Chartist movement such as Harney, along with a variety of political exiles from across Europe.

The Fraternal Democrats’ political platform, declared:

We denounce all political and hereditary inequalities and distinctions of castes…that the earth with all its natural productions is the common property of all; we therefore denounce all infractions of this evidently just and natural law, as robbery and usurpation. We declare that the present state of society, which permits idlers and schemers to monopolise the fruits of the earth and the productions of industry, and compels the working classes to labour for inadequate rewards, and even condemns them to social slavery, destitution, and degradation, is essentially unjust.

It made a call for internationalism:

Convinced that national prejudices have been, in all ages, taken advantage of by the people’s oppressors to set them tearing the throats of each other, when they should have been working together for their common good, this society repudiates the term ‘Foreigner,’ no matter by, or to whom applied. Our moral creed is to receive our fellow men, without regard to ‘country,’ as members of one family, the human race; and citizens of one commonwealth – the world.

As Harney explained:

Whatever national differences divide Poles, Russians, Prussians, Hungarians, and Italians, these national differences have not prevented the Russian, Austrian, and Prussian despots uniting together to maintain their tyranny; why, then, cannot countries unite for obtainment of their liberty? The cause of the people in all countries is the same – the cause of Labour, enslaved, and plundered…In each country the tyranny of the few and the slavery of the many are variously developed, but the principle in all is the same. In all countries the men who grow the wheat live on potatoes. The men who rear the cattle do not taste flesh-food. The men who cultivate the vine have only the dregs of its noble juice. The men who make clothing are in rags. The men who build the houses live in hovels. The men who create every necessary comfort and luxury are steeped in misery Working men of all nations, are not your grievances your wrongs, the same? Is not your good cause, then the same also? We may differ as to the means, or different circumstances may render different means necessary but the great end – the veritable emancipation of the human race – must be the one end and aim of all.

It is not any amelioration of the conditions of the most miserable that will satisfy us: it is justice to all that we demand. It is not the mere improvement of the social life of our class that we seek, but the abolition of classes and the destruction of those wicked distinctions which have divided the human race into princes and paupers, landlords and labourers, masters and slaves. It is not any patching and cobbling up of the present system we aspire to accomplish, but the annihilation of the system and the substitution, in its stead, of an order of things in which all shall labour and all enjoy, and the happiness of each guarantee the welfare of the entire communit (George Julian Harney, 1850, Red Republican).

Another prominent Chartist activist, Ernest Jones, gave the Chartist movement a more socialistic direction. He too was committed to the wider international context of the workers’ movement. In The People’s Paper of 17 February 1854, Jones wrote:

Is there a poor and oppressed man in England? Is there a robbed and ruined artisan in France? Well, then, they appertain to one race, one country, one creed, one past, one present, and one future. The same with every nation, every colour, every section of the toiling world. Let them unite. The oppressors of humanity are united, even when they make war. They are united on one point that of keeping the peoples in misery and subjection…Each democracy, singly, may not be strong enough to break its own yoke; but together they give a moral weight, an added strength, that nothing can resist. The alliance of peoples is the more vital now, because their disunion, the rekindling of national antipathies, can alone save tottering royalty from its doom. Kings and oligarchs are playing their last card: we can prevent their game.

In yet another article from The People’s Paper, March 3 1855, Jones explained:

Let none misunderstand the tenor of our meeting: we begin to-night no mere crusade against an aristocracy. We are not here to pull one tyranny down, only that another may live the stronger. We are against the tyranny of capital as well. The human race is divided between slaves and masters…Until labour commands capital, instead of capital commanding labour, I care not what political laws you make, what Republic or Monarchy you own – man is a slave.

Ernest Jones was also the prime mover in assembling what was called, the Labour Parliament. Jones in The People’s Paper for January 7, 1854, wrote:

Every day brings fresh confirmation of the need for a mass movement and the speedy assembling of the Labour Parliament. If it is delayed much longer, every place, Preston included, lost or at the best forced into degrading and weakening compromises…The Cotton Lords, at a ‘Mass Meeting/ of their own, unanimously resolved to support their brother Cotton Lords of Preston and Wigan with the full force of their funds. Under these circumstances it is class against class…It must, therefore, become manifest that unless the working classes fight this battle as a Class, that is, in one universal union by a mass movement, they will be inevitably defeated …The greater the lock-out, the wider the strike movement, the more national becomes the movement –the more of a class struggle it is rendered –and if the working classes once see that they are struck at as a class, their class instinct will be roused and they will rise and act as one man.

The Parliament met on March 6, 1854, at Manchester, attended by some fifty or sixty delegates, with the Parliament’s discussions lasting several days. Marx was to comment:

Some future historian will have to record that there existed in the year 1854, two Parliaments: a Parliament at London and a Parliament at Manchester – a Parliament of the rich and a Parliament of the poor – but that men sat only in the Parliament of the men and not in the Parliament of the masters.

Peter McDouall was another significant figure in Chartism who advocated the power of the ordinary worker. He explained:

The Trades are equal to the middle class in talent, far more powerful in means and much more united in action… The agitation for the Charter has afforded one of the greatest examples in modern history of the real might of the labourers. In the conflict millions have appeared on the stage and the mind of the masses has burst from its shell and begun to flourish and expand.

The question of what was to be the next step forward was one of great urgency. On this issue the Chartists were deeply divided. Many moderates refused to host McDouall’s meetings as he opposed alliances with the middle class.

Past defeats, he judged, could all be attributed to the fact that:

our associations were hastily got up, composed of prodigious numbers, a false idea of strength was wrought up to the highest pitch, thence originated a sense of security which subsequent events proved to be false, and why? Because no real union existed at the bottom.

McDouall’s proposal was to turn to the working class, as only it had the necessary potential strength. He believed the Chartists should win over the newly-forming trade unions and use them. However, some of his Chartist critics saw the trade unions not as allies but as rivals, regarding union activity as a diversion, side-tracking people from the real struggle for the franchise.

McDouall was yet another Chartist who recognised the international aspect of their struggle:

Let all who have possessions in India, or all who profit by what you call ‘our Indian possessions’ be off to India, and fight a thousand battles for them as they like… but let them not mock our degradation by asking us, working people to fight alongside them, either for our ‘possessions’ in India, or anywhere else, seeing that we do not possess a single acre of ground, or any other description of property in our own country, much less colonies, or ‘possessions’ in any other, having been robbed of everything we ever earned by the middle and upper classes…On the contrary, we have an interest in prospective loss or ruin of all such ‘possessions’, seeing they are but instruments of power in the hands of our domestic oppressors.

1848 was Europe’s Year of Revolutions and as Marx and Engels released their Communist Manifesto, McDouall was addressing rallies, spurring people into action. After he spoke in Edinburgh, there were street disturbances with shouts of Vive la Republique! and Bread and Revolution.

Many before Marx understood the terrible human impacts of the capitalist system — all the poverty, misery, madness, inequality and its injustice. Socialists, who reject capitalism, follow a similar strategy as those Chartists militants before us and struggle for any improvement even if we know that it may disappear overnight. But to stop struggling would only make workers worse off than we are now.